- What's On

- Collections

- Research

- Stories

- Visit us

- About Us

- Get involved

South Australia has always prided itself on being a progressive state. In 1894, after a ten year battle, women here were granted the vote, second only after New Zealand which had granted the vote to women a year earlier. However, South Australia also gave females the right to stand for parliament, and this was a first. The legislation was known as the Constitution Amendment Act, 1894. The Act became law when Queen Victoria gave royal assent early in the following year. Women voted for the first time at the next election, in 1896.

One of the key figures in the campaign for women's suffrage was Mary Lee but she was certainly not alone. Other key figures were Rose Birks, Elizabeth Nicholls, Mary Colton, Catherine Helen Spence and men such as Joseph Kirby, Edward Stirling, Sylvanus Magarey, and John Cockburn. But there was also vital community support from many now-forgotten individuals and organisations. Nonconformist denominations, such as Methodists, Baptists and Congregationalists were strong supporters. A number of prominent clergymen and members of Parliament lent their support. In the broader community, literary groups, writing circles, youth groups and young men's societies enthusiastically discussed and debated the issues.

The key organising group was the Women's Suffrage League. They in turn had support from other community groups – the temperance groups, trade unions and churches. The Woman's Christian Temperance Union was a powerful ally, especially in the last five years of the struggle, as was the men's Temperance Alliance. The United Trades And Labor Council Of South Australia, and the Working Women's Trade Union also committed to the cause. The United Labor Party, formed in 1890, had a chequered but increasingly strong working relationship with the League. Other less well-known groups included the Working Women's Distress Fund, the Working Women's Shirt-making Co-operative, the Women Teachers’ Association, and the Woman's League. The word to remember is ‘organisation.’ In the end it was was this that won women's franchise.

There had been a lot of opposition to female suffrage, particularly from politicians, and those in the liquor trade. The opponents of suffrage were disparaging, patronising and at times, full of bile. Their anger and contempt for the rights of women emerged in numerous newspaper letters and articles, in Parliamentary petitions and in Parliamentary debates. One of the worst was politician Ebenezer Ward. To the bitter end, he put his skills to good use trying to scuttle the suffrage bills. In 1894, when told in Parliament that the electors of South Australia wanted the vote for women, he replied ...

'Nonsense! The demand comes from a lot of fanatics and faddists who call themselves social reformers, and assume to represent the will of the country. They are not merely a few females who are not feminine, but are associated with and supported by a few males who are not masculine!'

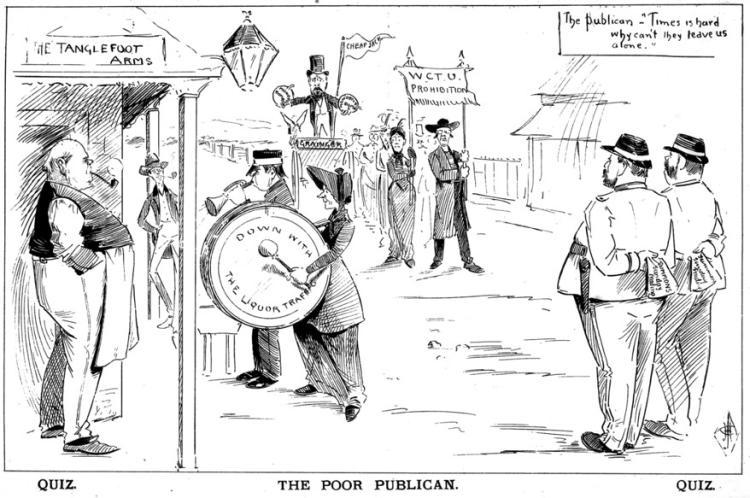

Others, like brewer Edwin Smith opposed the women's vote for financial reasons. The Women's Suffrage League worked closely with the anti-alcohol Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to win the vote. Brewery owners feared the Temperance 'white ribboners' would close down their businesses. This cartoon appeared in satirical newspaper the Quiz and the Lantern in Oct 1894. Here you see the WCTU marching down the street. The ‘poor publican’ is being assailed on his own verandah. The hapless gent running the cheapjack stall, is politician Henry Grainger, who was as enraged by suffrage as Ebenezer Ward, and from his public comments, appears as much of a misogynist.

In October 1893, satirical newspaper the Quiz and the Lantern published the cartoon below. Many opponents, like politician and businessman, Vaiben Solomon, genuinely believed that if women were enfranchised they would neglect their homes and children and stop tending to the comforts of their husbands, fathers and brothers. Women as well as men, believed that domestic harmony was under threat from unfeminine, mannish suffragists.

There was real fear that these newly enfranchised harpies would turn the world upside down. They would turn to relaxations like smoking, gambling, and serving tea (or something stronger). Horror of horrors, they might start playing the banjo and having an all-round rollicking good time, with not a man in sight or required!

The opponents of female suffrage had predicted dire consequences for women who turned up at the polling places. However the 1896 election went smoothly. The women of South Australia enthusiastically exercised their right to vote for the first time. In fact the percentage of women who both enrolled and attended the voting booths, was slightly higher than the percentage of males. And did you know the Dominican nuns at North Adelaide all followed their Mother Superior to the voting booths ? ( The Register, 27 April 1896, p. 5). To the great surprise and disappointment of the anti-suffragists, there was not a single riot. The sky did not fall, women did not desert their husbands in droves, and the world did not end!

Winning the vote was a giant step forward but there were several other significant innovations that strongly affected the lives of women in South Australia, all of which had occurred before the vote was won. The first related to women's legal rights. Under English Law, when a woman married she came under the coverture or supposed protection of her husband (or baron or lord). From the moment she said ‘I do’ a married woman ceased to be a legal entity in her own right. In other words a married woman, under coverture, had virtually no rights. For the most part, all that she owned, inherited or earned became the property of her husband, as were any children of the marriage. There were changes to the Act over time, mainly in relation to divorce and children. But the most important change didn’t occur until the British Parliament passed the Married Woman’s Property Act, 1882. This model was gradually adopted in Australia. The changes to women’s rights gave married women back their own legal identity and much greater rights to their own income and property. This increased freedom went on to inspire change in other areas.

The other two innovations involved the education of girls and young women. Both provided opportunities to learn and imagine new ways of being and becoming. In 1879 after extensive lobbying by writer and social activist Catherine Helen Spence, educator John Hartley (headmaster of Prince Alfred College), and public health proponent Dr Allan Campbell, the colonial government had established the Adelaide Advanced School for Girls.

Opened in 1879, this was Australia’s first state-funded secondary school for girls, although it was not free. For those who could attend, it enabled study beyond primary school to matriculation level. (Primary school education had been made compulsory five years previously and government-funded schools had been built to provide it). Private schools existed to provide secondary education for boys but were beyond the reach of most. At least the new Adelaide Advanced School now provided opportunities for some girls (those whose families could pay the fees) to prepare for university entrance. The school became part of the co-educational Adelaide High School in 1908. Many of its students went on to become university graduates.

The colony's first university had opened in 1874. Land was reserved on North Terrace and the University of Adelaide's classes were taught in Grote Street at the Teachers Training School until 1881. Students then moved into the institution's first North Terrace building, although it was not yet completed and did not open officially open until April 1882. The University of Adelaide had intended from its inception to admit women to degrees and also to provide more modern practical subjects such as science and engineering, as well as the more traditional university subjects of Latin and Greek. The trend towards science, technological subjects and modern languages was growing in Great Britain but the proponents of the classics were not enthusiastic. Unfortunately when our first university tried to gain the Royal Charter for its Act of Incorporation, the decision lay with the Colonial Secretary in London and the University's plan to modernise the curriculum was not acceptable. Even less acceptable was the notion of conferring degrees upon women. The Colonial Secretary said no and so these radical proposals were reluctantly removed. Without the British monarch's Letters Patent the new South Australian degrees would not be valid overseas. The University Council and staff persisted but it took some years for change to come. Meanwhile a few determined women attended classes without hope of gaining their degrees. In 1876 Chancellor Bishop Short reported that 33 of the institution's 52 non-matriculated attendees were women. In 1880, the University of Adelaide Degrees Act was altered to include the following words ...

'In the Adelaide University Act, words importing the masculine gender shall be construed to include the feminine.' ~ Mackinnon, Alison: The New Women, Adelaide's early women graduates, p 19.

In 1881, the Act was altered again, this time to enable Adelaide University to confer degrees 'on any person, male or female'. (op cit. p 23). The flood gates may have opened but only a trickle of young women passed through in the early years. In fact, by 1900 only two dozen women had actually graduated. Still, it was a beginning. South Australians were beginning to seek out new pathways. The Proud family are just one example.

These are the Proud women. The daughters were very young when suffrage was won but it contributed to their later success. This 1910 photograph shows Annie on the left, the only surviving child of Cornelius and his first wife, Mary Ann (nee Lines). Next to Annie is Emily Dorothea who was awarded the Catherine Helen Spence overseas scholarship for women, then became a lawyer and later married Gordon Pavey. In the centre is Millicent who graduated with a Master of Arts from Adelaide University. Seated second from right is Emily, second wife of Cornelius Proud. Emily was the mother of Dorothea, Millicent and Katherine (who appears last on the right). She became the first woman to earn a Diploma in Commerce from Adelaide University and later married Hills orchardist, Alec Magarey. Katherine was also made a life member of the Country Fire Service.

Cornelius Proud and his second wife Emily were staunch advocates of wome's suffrage. Initially employed by the Register, Cornelus later became a stockbroker. Emily had herself attended classes at Adelaide University at a time when women were unable to be granted degrees, no matter how hard they studied. Cornelius drafted the wording of the great Women's Suffrage petition. In August 1894 he delivered the petition to Parliament House. He walked with it from Gawler Place, quite a feat because it was a huge. When unrolled, it was close to 140 feet in length.

Cornelius delivered it into the arms of George Hawker who was known as the 'father of the House'. The petition was then presented to the House of Assembly. The Advertiser reported ...

Mr GC Hawker presented a bulky petition, said to have been signed by 11,600 persons in favor of granting the franchise to women on the same terms as men. A cheer greeted the solid roll, neatly tied up in yellow ribbon as it was handed by the presenter to the clerk in the tender manner in which a baby is handed to the parson at the font.

In the Victorian era, and beyond, success for most women was measured by duty, purity and service in the domestic sphere and religious piety, modesty and service in the social. Yet there were always women who imagined different forms of success, in business and professions such as education, medicine, welfare, law and commerce. Social and educational reforms and the women's vote, opened up a world of new possibilities. The term 'New Woman' was coined. It took support and funds, usually from family, for these 'new women' to pursue work paths and professions usually reserved for men. But it was their own stamina, dedication and determination that allowed them to overcome prejudice and blaze new trails for coming generations. It was quite a feat when you think about it.

Writer: Isabel Story, Community Engagement Librarian