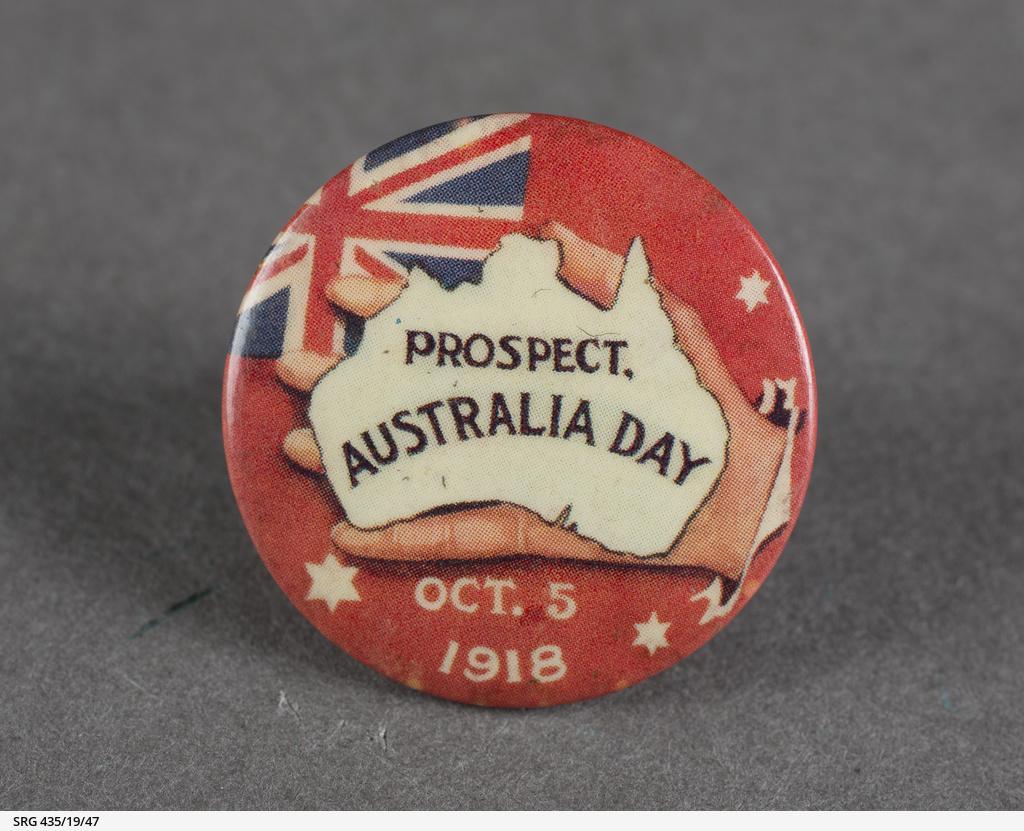

The State Library holds many of these wartime buttons, most of which have been photographed so we can share them online.

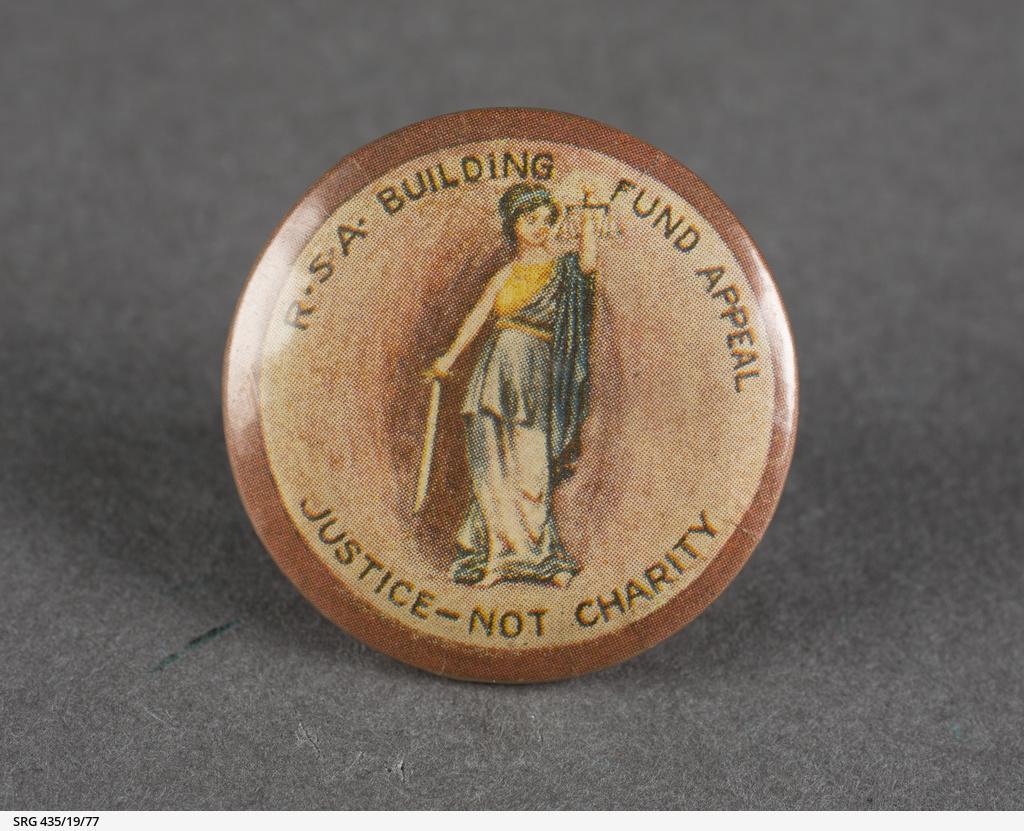

- The RSL collection (SLSA: SRG 435/19) is the most recent to be made available for online viewing. It contains 155 images of individual button badges.

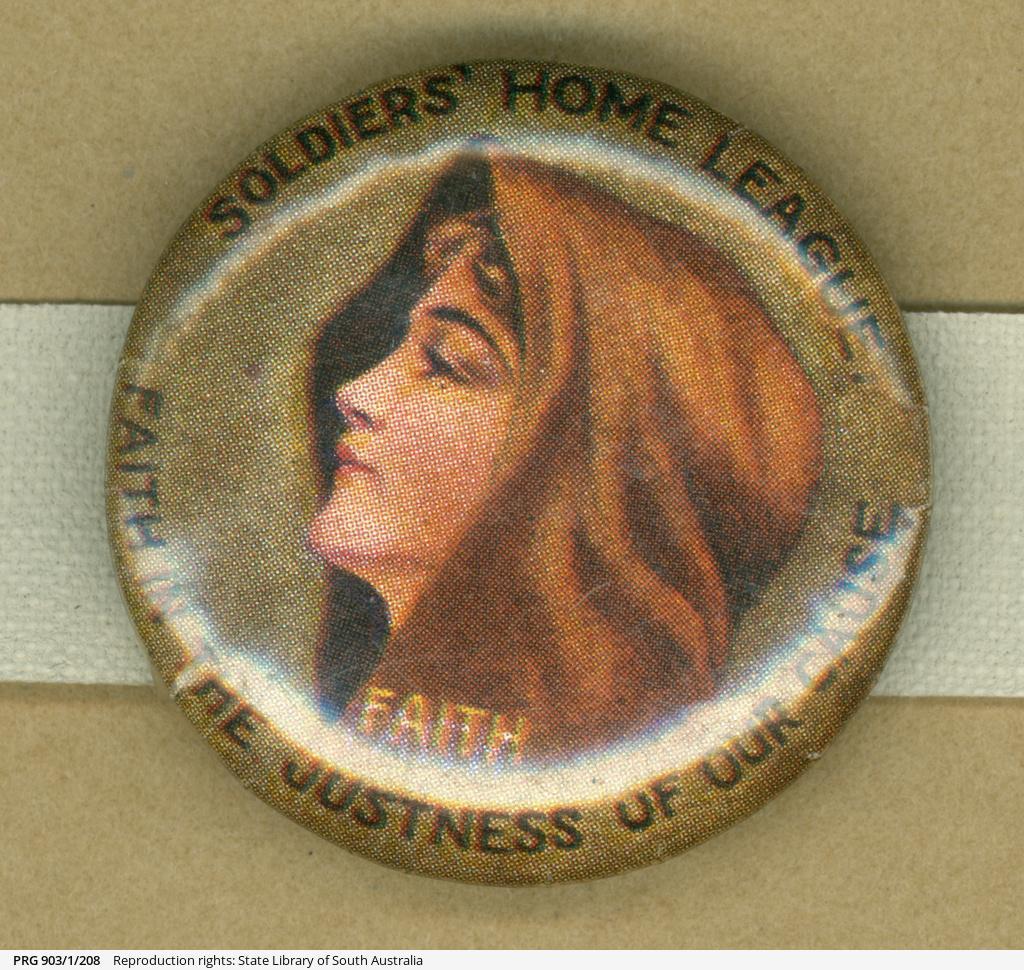

- The Lottie Michell collection (SLSA: PRG 903/1/1-208) holds 208 items.

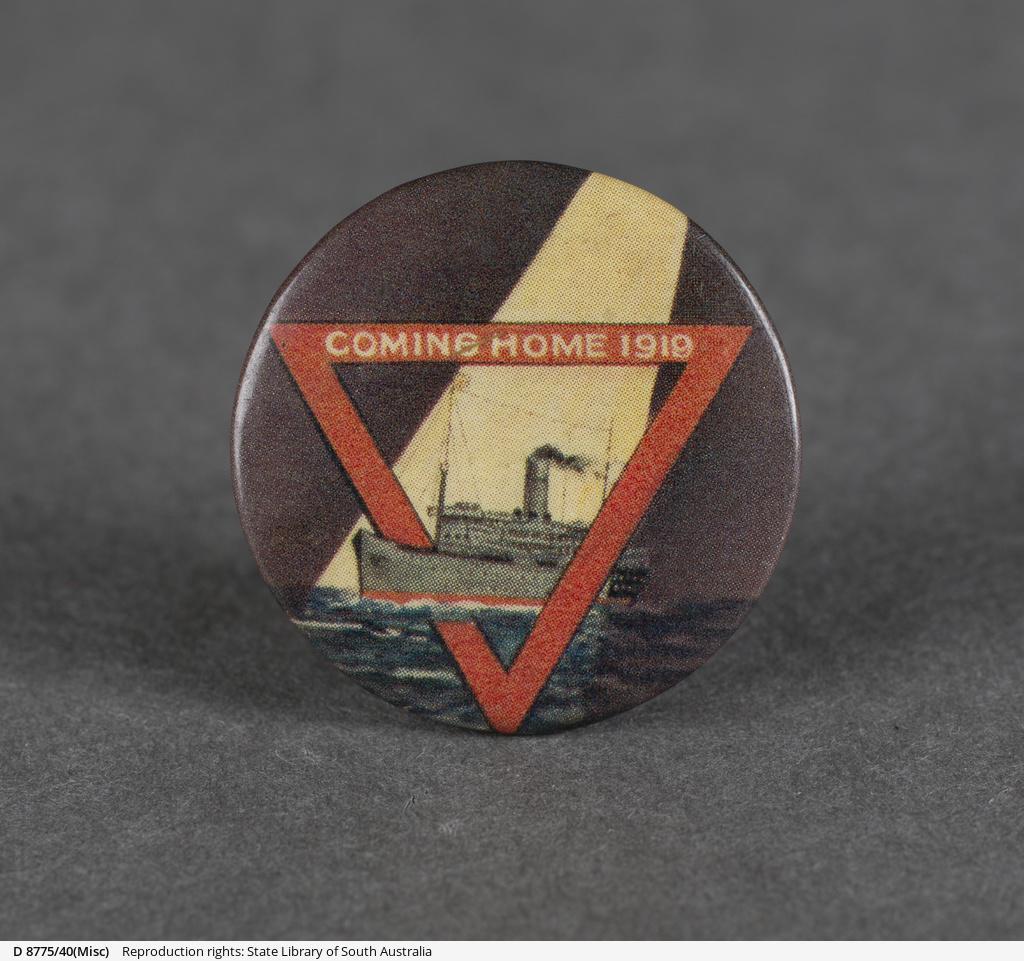

- The Alan Greenlees collection(SLSA: D 8775/1-73(Misc)) brought together a set of 73 badges while working at Broken Hill.

- Sir Josiah Symon’s family arranged and framed (SLSA: PRG 249/14/1) 477 button and regimental badges.

There is some content overlap between the different collections.

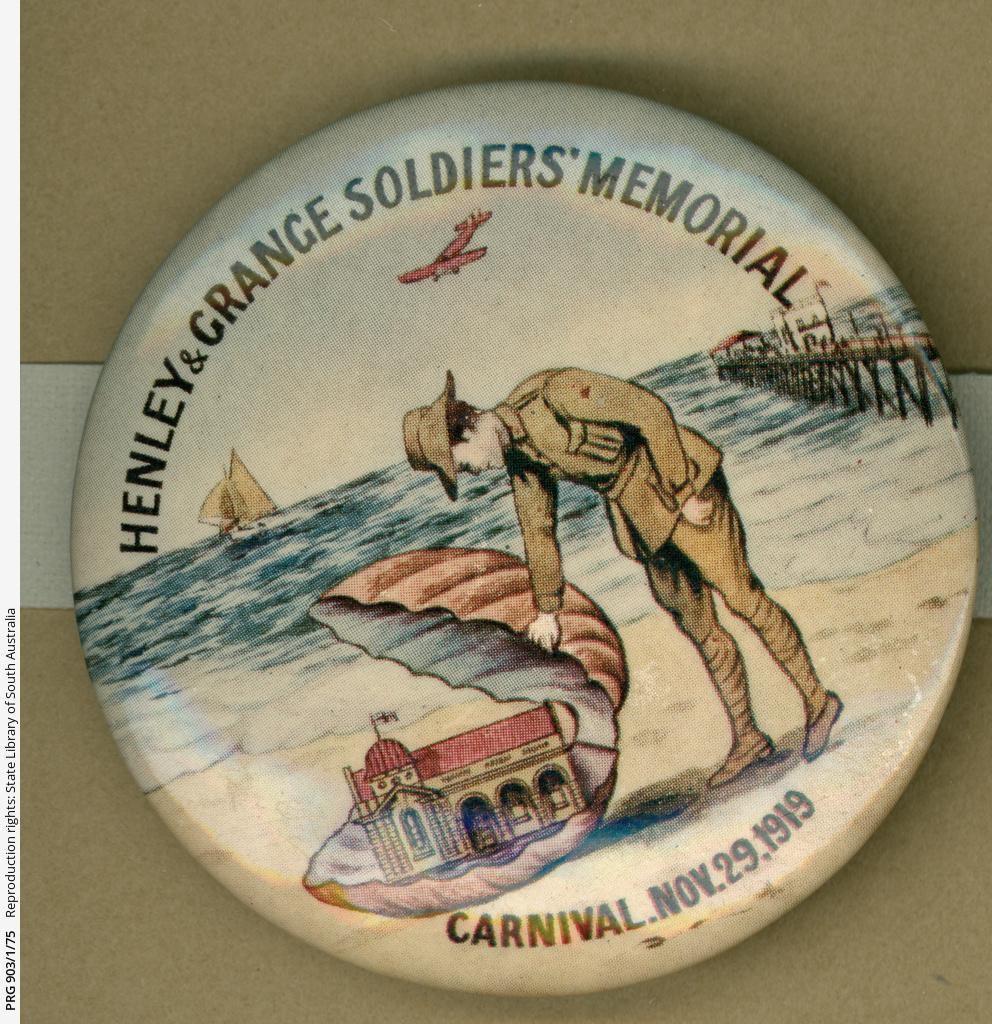

The war led to a boom in mass production. Soon there were celluloid buttons for every imaginable support group. And this was just in South Australia. The pattern was repeated across the country. On the Australian home front, a fighting chest was raised through government war bonds and loans. But more was needed. War was declared in 1914 and multiple organisations sprang into gear to raise money and support serving men. Singers, dancers, musicians, actors, artists, and sporting figures donated their time. They staged carnivals, parades, concerts, plays and fancy-dress balls. Regional and city churches held fetes and garden parties, sporting clubs organised tournaments and exhibition matches. Badges were sold by volunteers, mainly women, in the streets, at fund raisers and entertainment venues.

WW1 Badge Sellers, Adelaide. SLSA: PRG 280/1/15/34

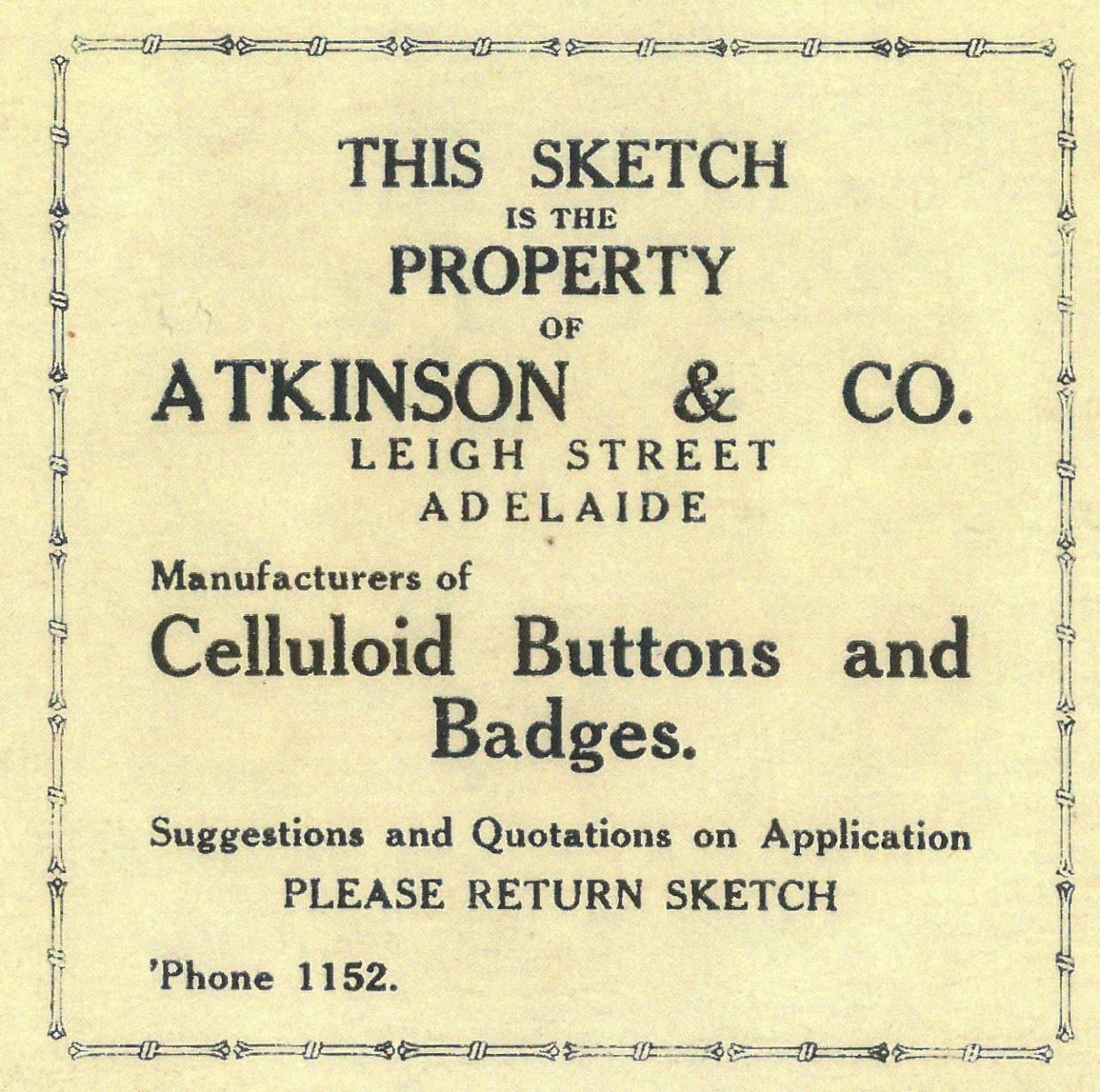

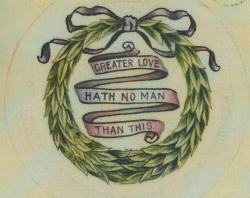

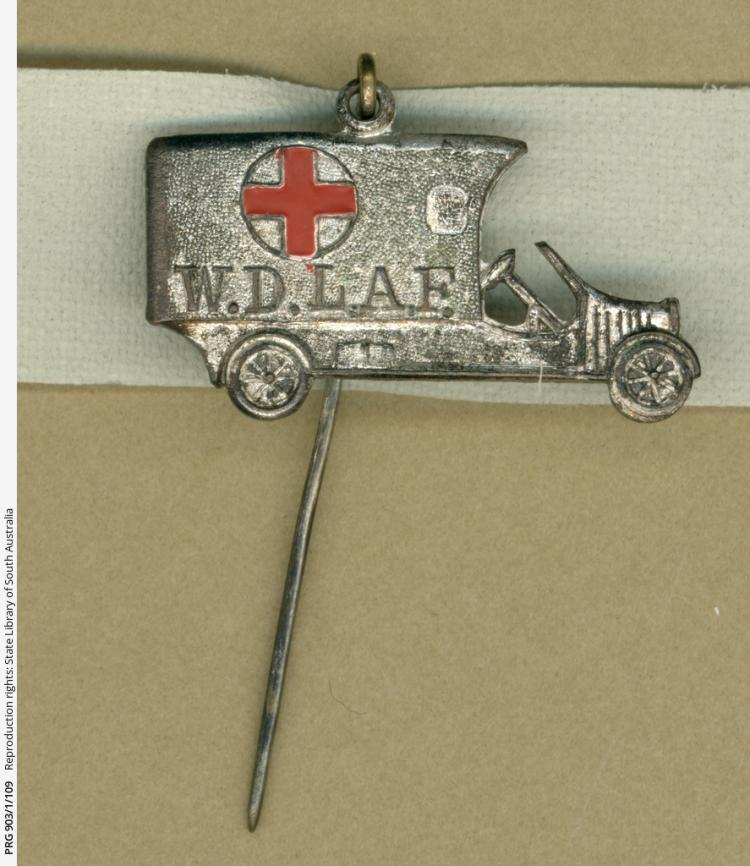

Designs developed over time. Some displayed plain lettered slogans, photographic images and some were miniature artworks. They may have been locally designed or more often, designed by artists employed by the manufacturers. Not all badges were metallic or round. Some were made of celluloid or cardboard in various shapes and sizes. This metal stickpin lapel badge was a fundraiser for the Wattle Day League Ambulance Fund.

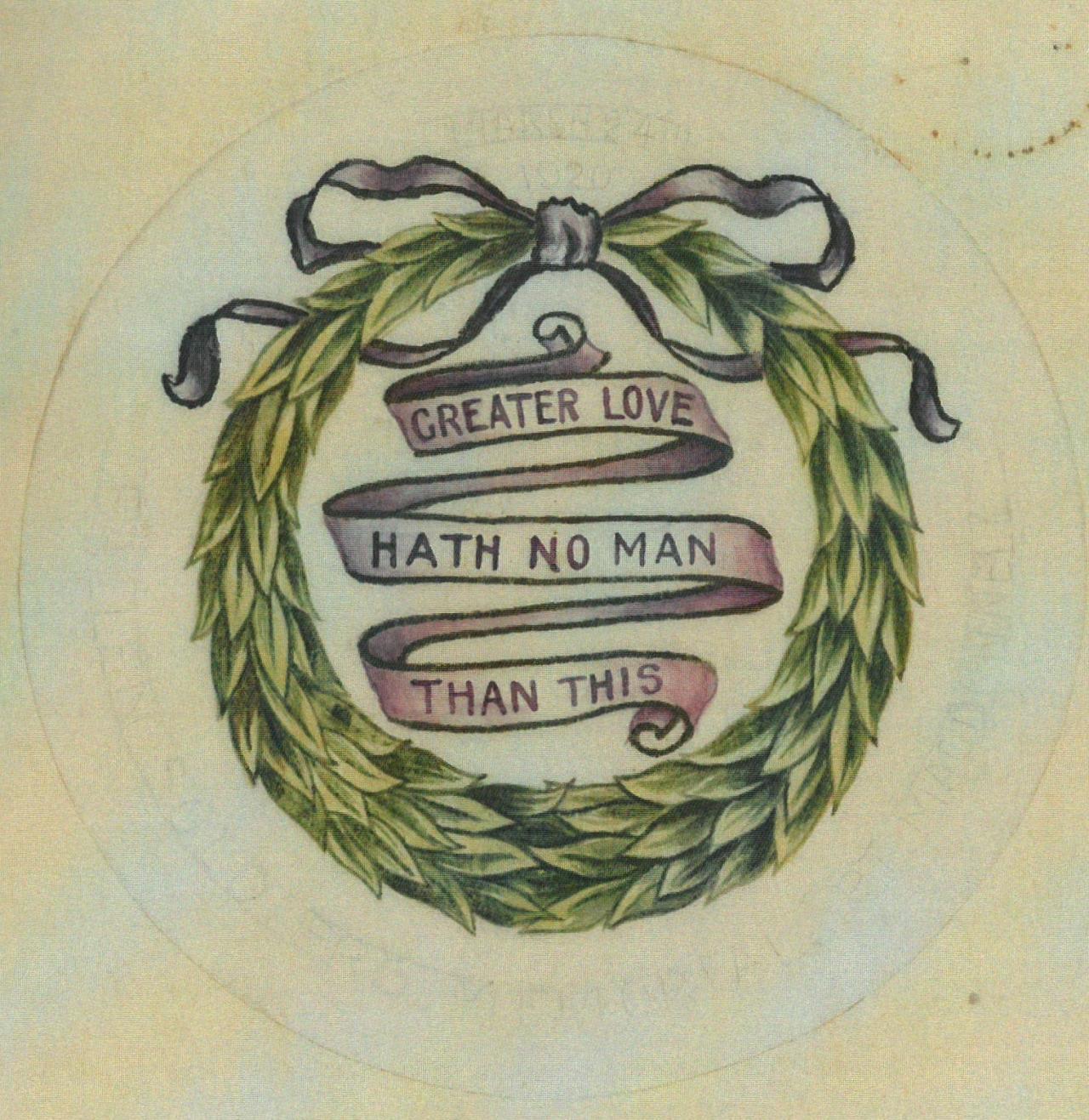

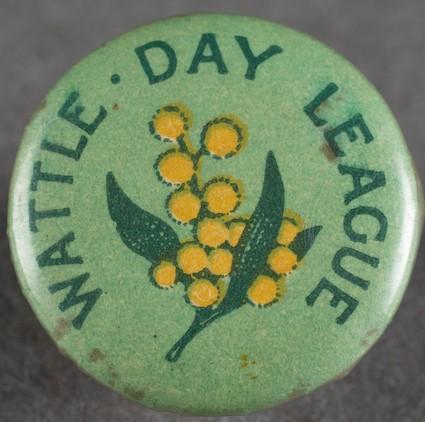

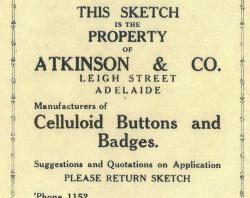

One of the first producers in Australia was AW Patrick. The company made badges, lapel pins and other memorabilia in Sydney and Melbourne, and also opened in Adelaide as demand grew. Atkinson & Co. was a similar local manufacturer. Within the Library’s archival collection are a number of designs by Dora Whitford (D 8143) who was an artist employed by Atkinson’s during and after the war.

Throughout Australia men and women sold badges, dolls and other small items in the streets and at entertainment venues. People donated money, goods and time to myriad small groups which supplied comforts such as tobacco, biscuits, socks and soap to those serving overseas. Eventually overlap and difficulty in getting goods to the troops and medical personnel led to the formation of the Australian Comforts Fund (ACF) in 1916 which was designed to bring state organisations under one national umbrella.

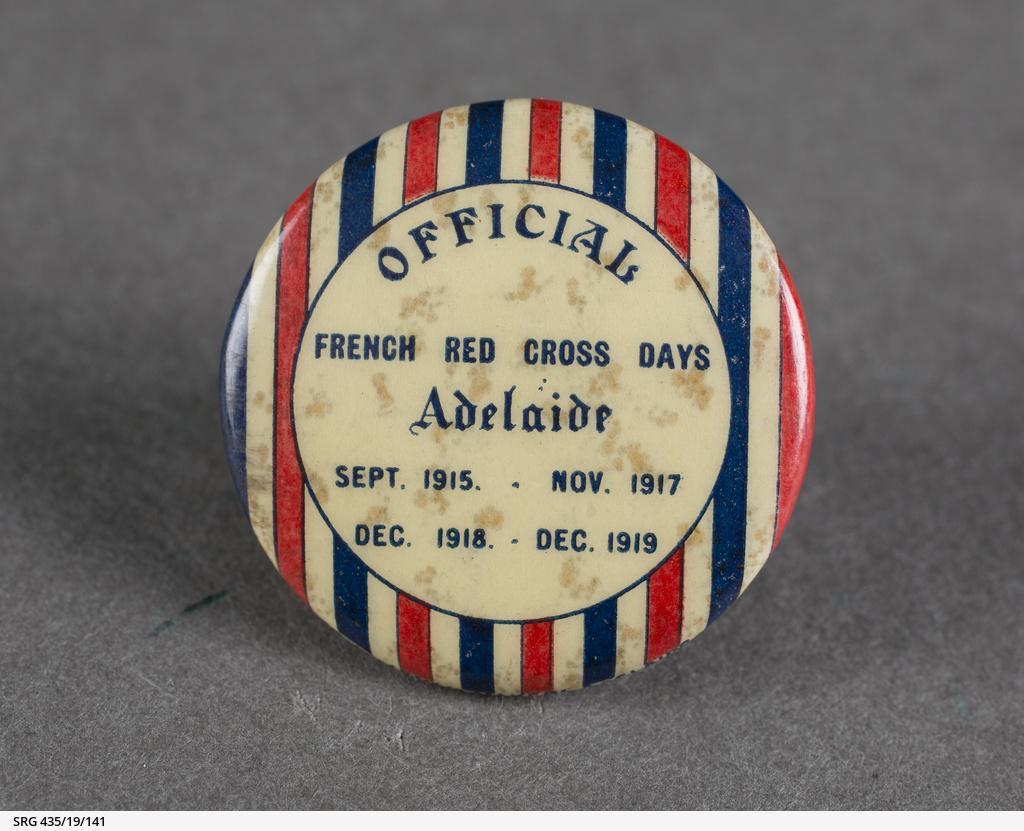

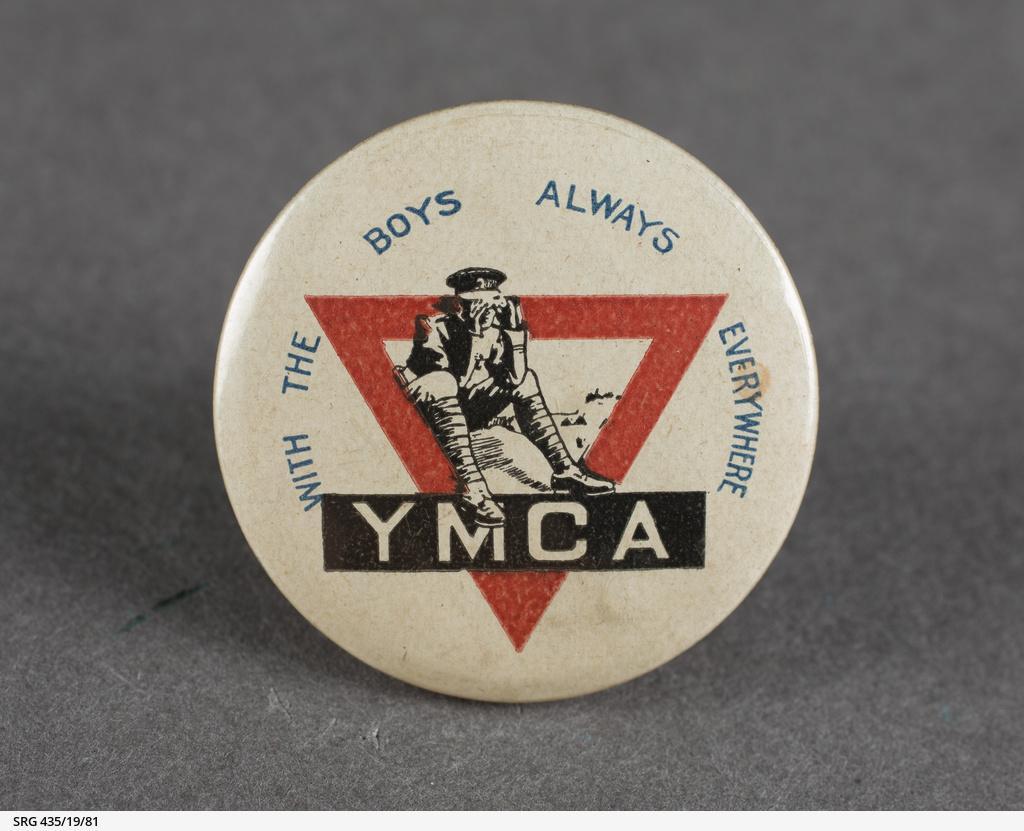

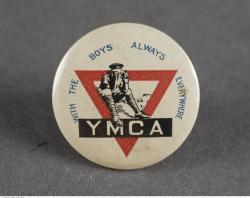

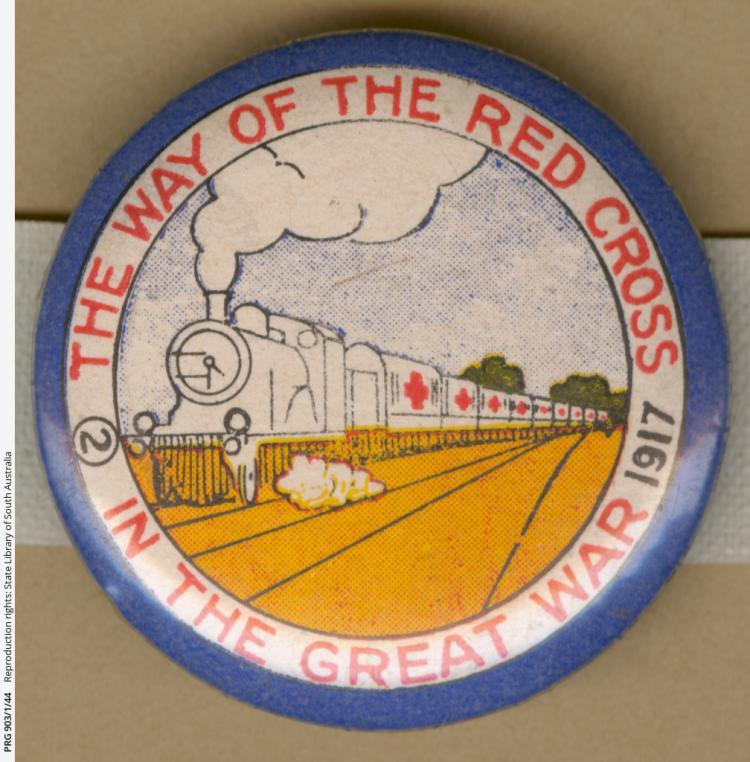

While the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) provided recreation activities and entertainment for the military in training camps and at the Front, the Red Cross provided hospital aid, clothing and comforts for the wounded. Both were, and are, international organisations.

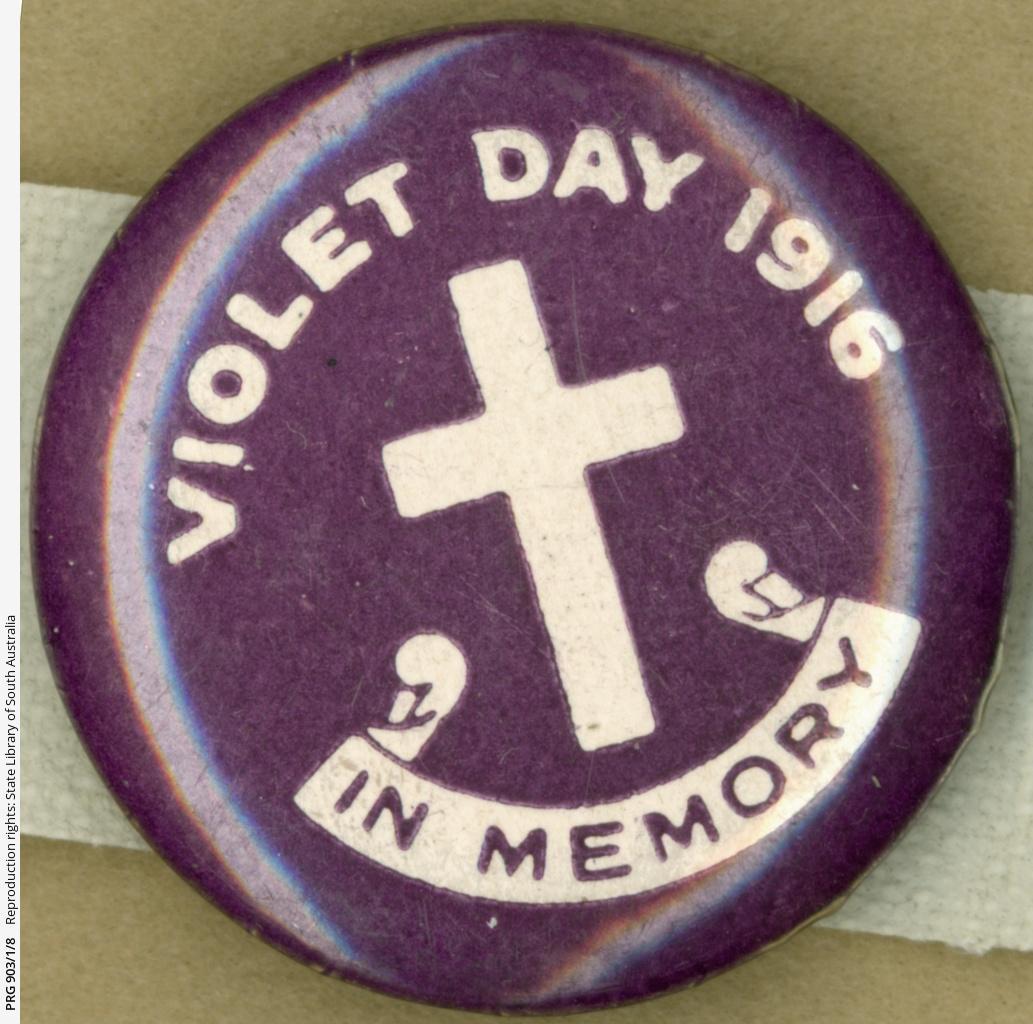

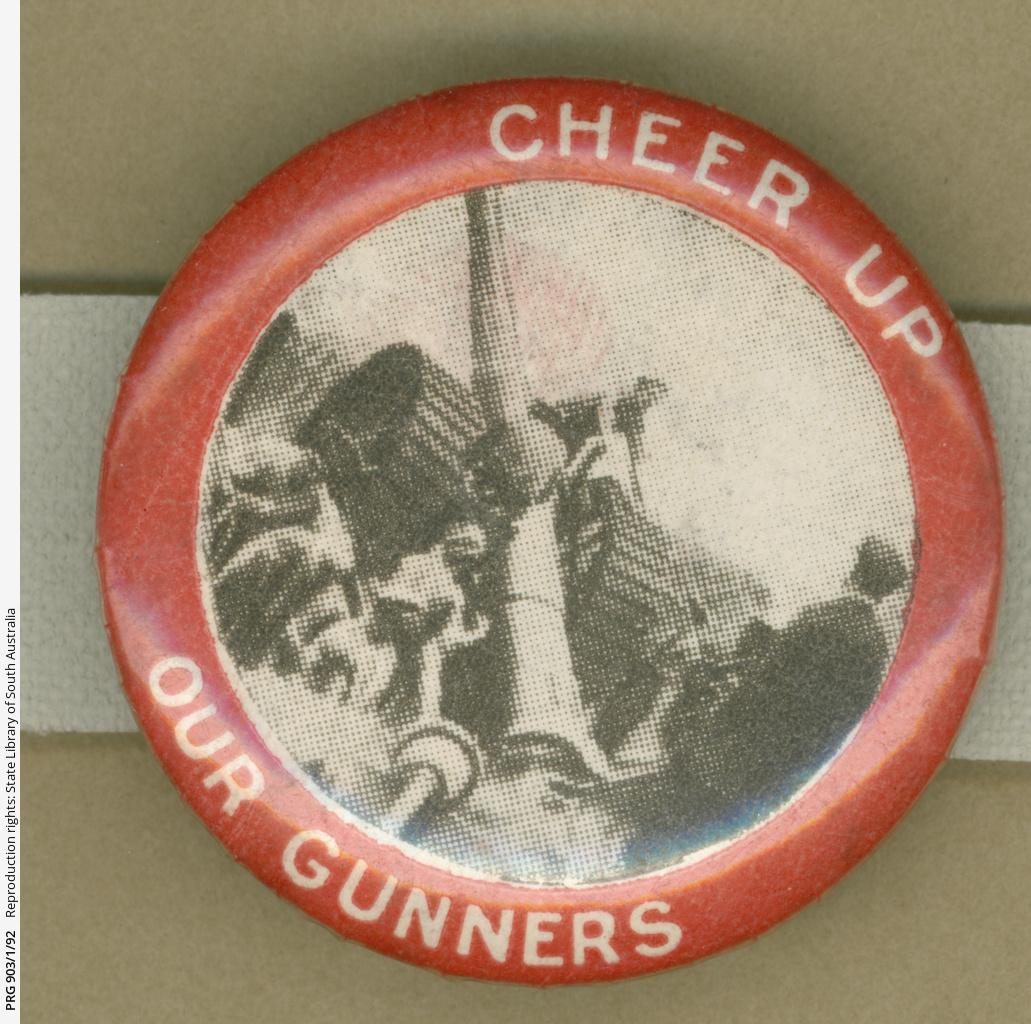

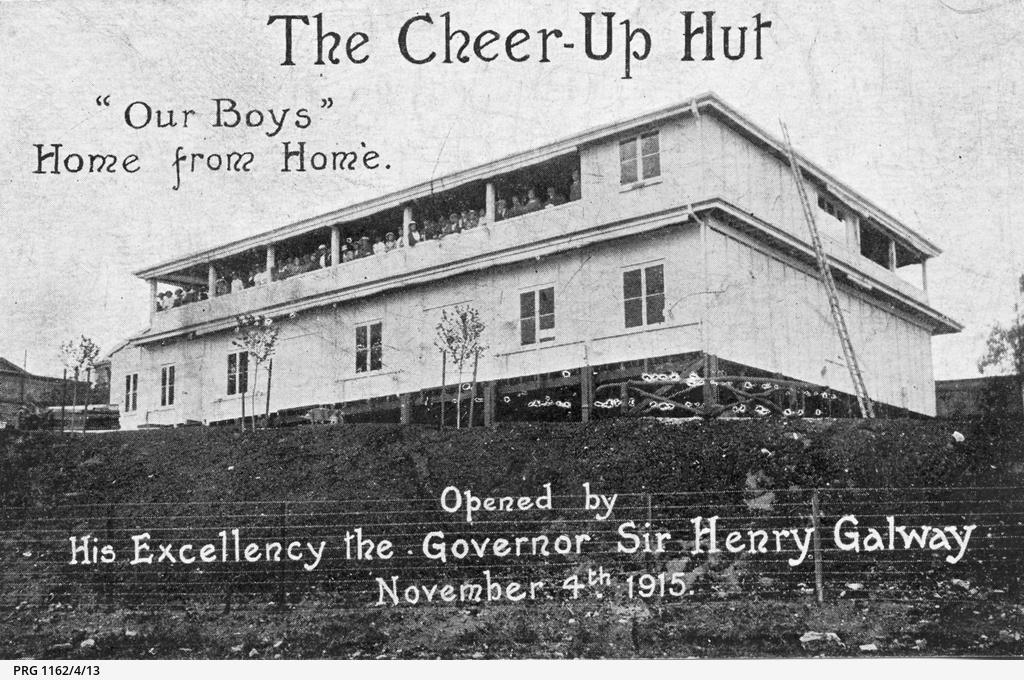

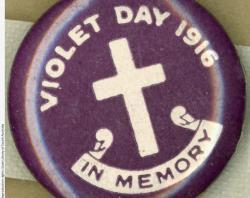

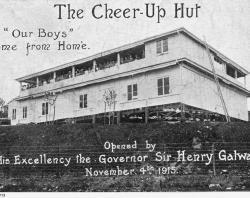

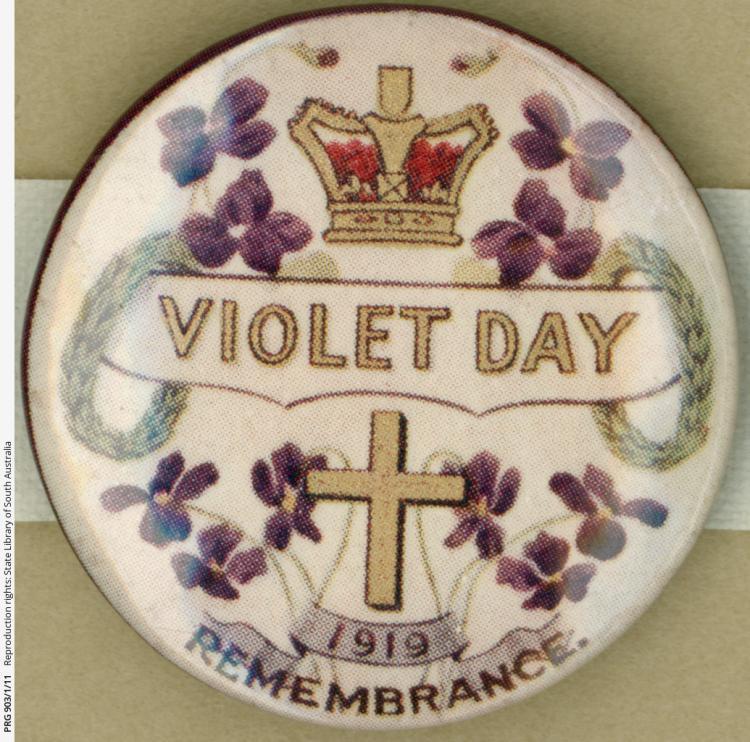

At a local level many support groups sprang up. The best-known of these was the Cheer-up Society which soon had branches throughout South Australia. Mrs Alexandra Seager initiated Violet Day in 1915, with the sale of small bunches of violets in remembrance of the wounded and fallen. Violet Day then became an annual event to raise funds to build and maintain the Cheer-up Hut behind the Adelaide railway station. The Cheer-ups provided a welcome, meals and entertainment for tens of thousands of soldiers in training, in transit or on leave.

At the beginning of the 1914 – 1918 war, most public donations were sent directly to an overseeing committee for the various organisations. As the war continued, specific days were designated for collecting from the public. Badges became an ideal way to promote a specific organisation or cause. From Federation onwards various groups including the Australian Natives’ Association and Wattle Day League (WDL) had lobbied for a national day. During the war their focus shifted to supporting forces overseas and commemoration. The WDL raised funds to purchase ambulances and provided help to injured veterans in hospitals. An Australia Day badge was first introduced on 30 July 1915 to raise funds for the Red Cross in order to support ‘our wounded heroes’. (This was not the government-declared Australia Day which officially began in 1946 and is held in January each year.) There were also many local variants of the Australia Day and other buttons.

Some days were dedicated to specific branches of the military such as the navy or the army. Some were calls to arms and depicted battlefield weapons such as tanks, planes and ships. Many carried a patriotic slogan or a reminder to Australians to do their bit. ‘I will help until the war is won.’ Is one example. Some tugged at the heartstrings with messages such as ‘Somewhere in France’ alongside an image of a lone soldier on a battlefield.

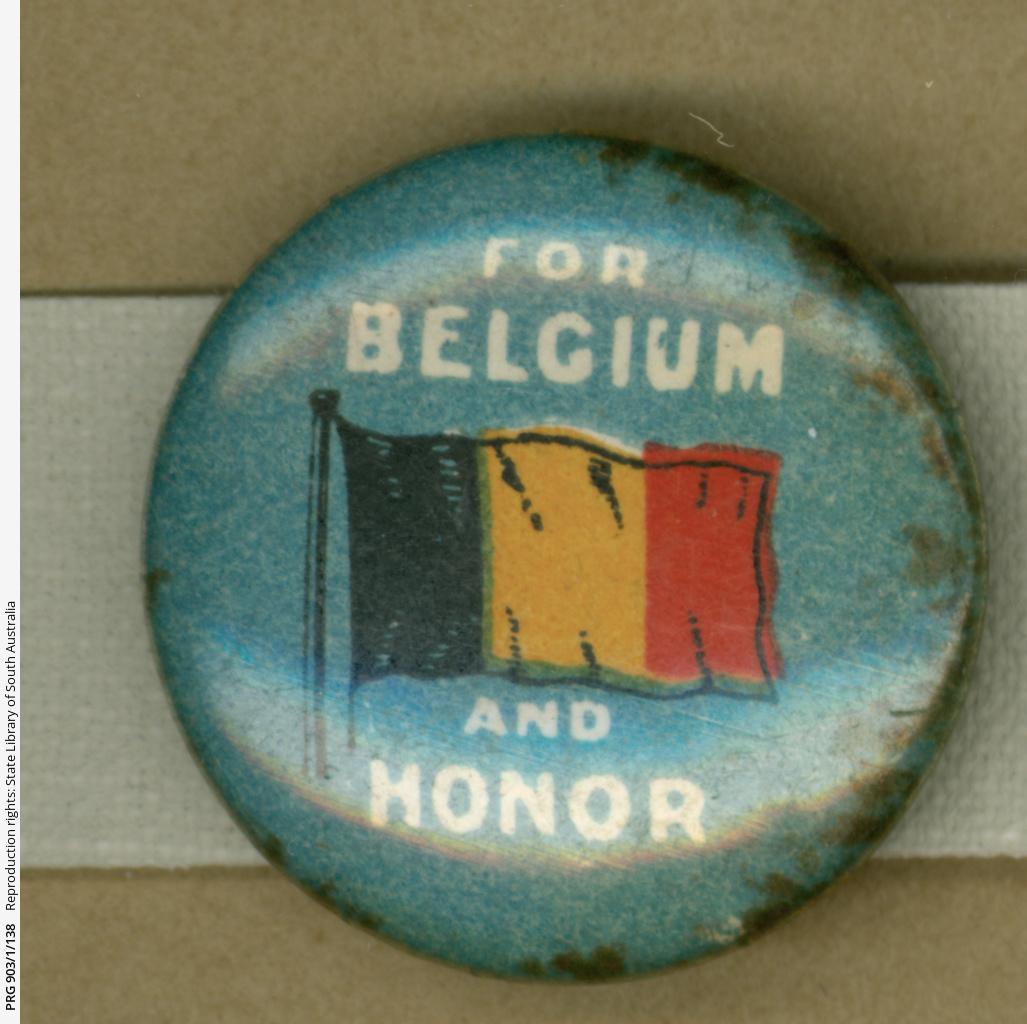

Support for Britain’s Allies was also a feature of the war effort. Money was raised for the civilian victims of war, particularly in Belgium and France where entire villages and towns had been destroyed.

Badges were also an opportunity to publicize the losses inflicted on civilians by the invading enemy. On one Red Cross appeal badge a woman and children are shown huddled against a wall with a backdrop of ruined buildings.

Patriotic slogans reinforce faith in the ideals of king and country, heroism and the war as a just cause. Badge artwork also emphasises motherhood, nurturing, and the necessary sacrifice of loved ones for a greater good. The Red Cross reminded people of their role with ’Red Cross, Greatest Mother in the World’ and its accompanying artwork. Symbolic representations of the loving and protective mother figure occur throughout the war and post-war years, particularly on badges associated with the Red Cross and Army Nurses but also in depictions of women and children as civilian victims of war.

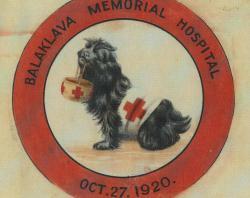

As the war continued, wounded service personnel began to come home. Increasing effort was put into organisations such as the Returned Soldiers Association (RSA, later the RSL). Fund-raising efforts turned to building and equipping rehabilitation hospitals and supplying fresh food and amenities to the patients.

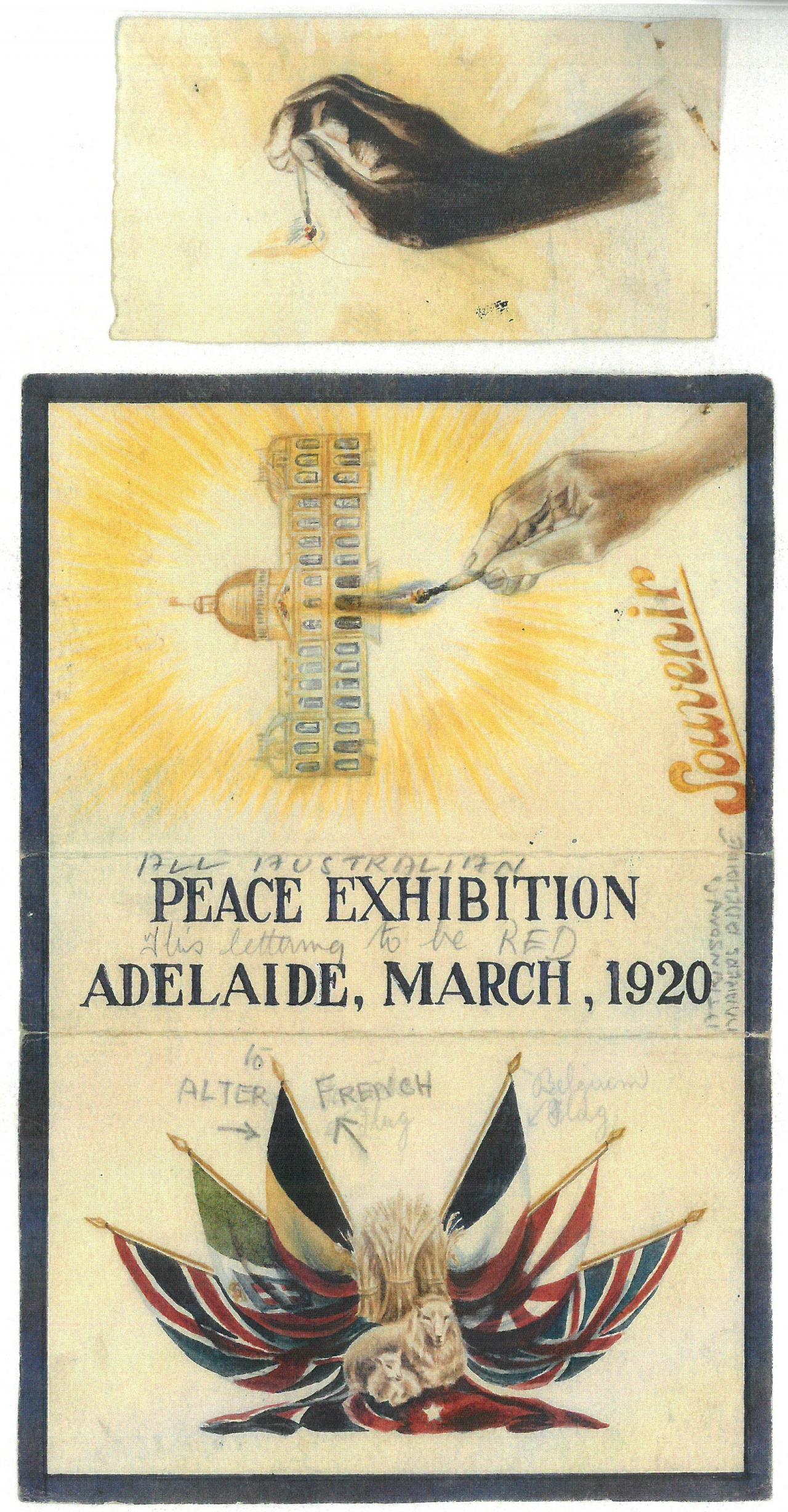

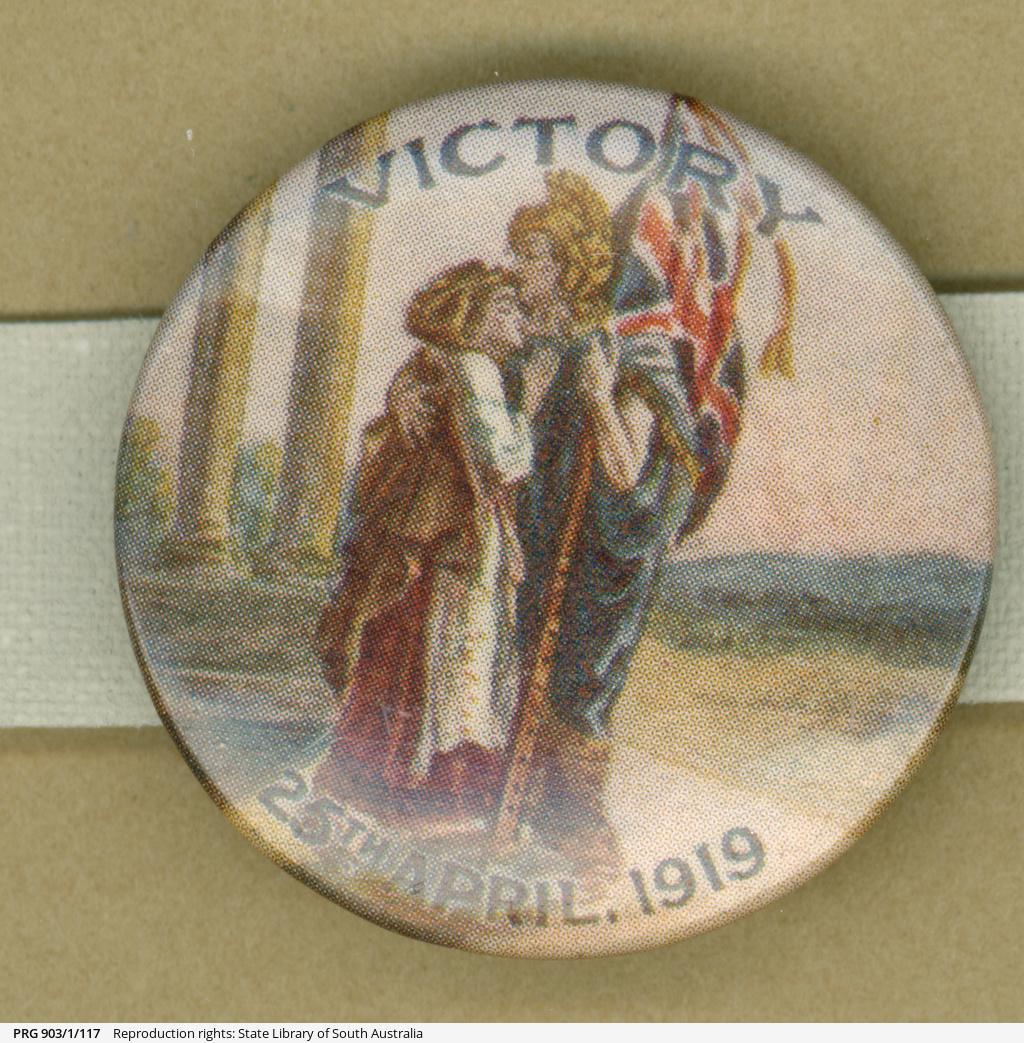

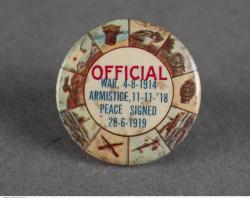

Finally, the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918. After four anxious years soldiers, sailors, airmen and nurses began to return home. Community support remained vital as the real cost of war became apparent. Even more hospital wings were required, as well as rehabilitation facilities, job re-training, and rest homes for those too damaged to ever work again. All of this had to be funded, and in response button badges continued to be produced, this time not to support the war effort but to ameliorate some small part of the damage done.

Repatriated service personnel, their mothers, wives, widows and children needed help, families needed to celebrate war's end but also to grieve. The country wanted to honour its war dead and wounded. Monuments were erected and memorial parks were designed as places where those who were left to grow old, could go to remember.

With the declaration of peace, tens of millions believed that they had endured the war to end all wars. Few could have foreseen that just over twenty years later global conflict would begin again.

In 1918 those who had lost loved ones, homes and communities must have wondered how those losses could be so quickly forgotten, the hope of peace so easily shattered and the threat of another global conflict still possible. More than a century later it seems that some questions still have no answers. Perhaps they never will.

Violet Day Remembrance badge, 1919. SLSA: PRG 903/1/11