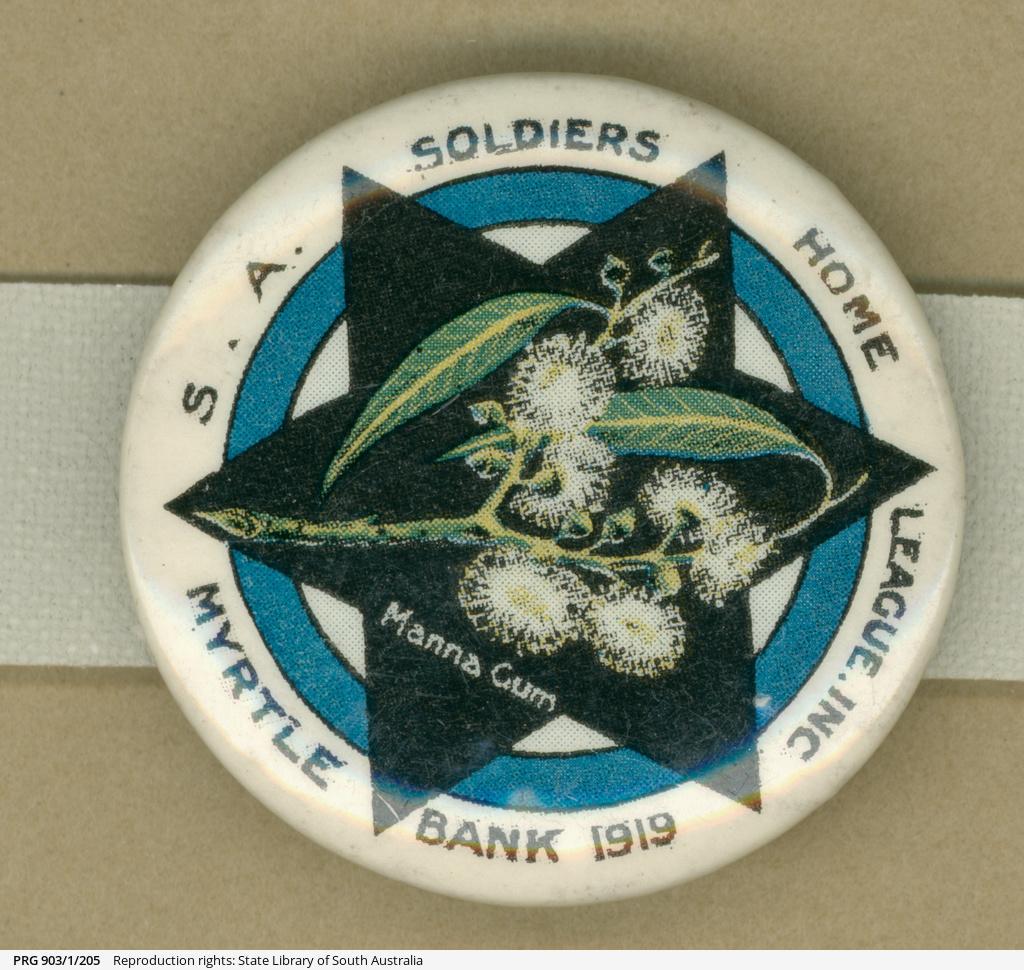

From the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, native fauna and flora were becoming increasingly popular as living plants, depictions in art and furniture and as patriotic emblems.

Wattle day

On 20 September 1889 William Sowden, Vice-President of the Adelaide branch of the Australian Natives’ Association, put forward the idea of a Wattle Blossom League. In fact silver wattle had first been used as a 'national' symbol in Hobart, then 'Hobart Town' at a regatta in 1838.

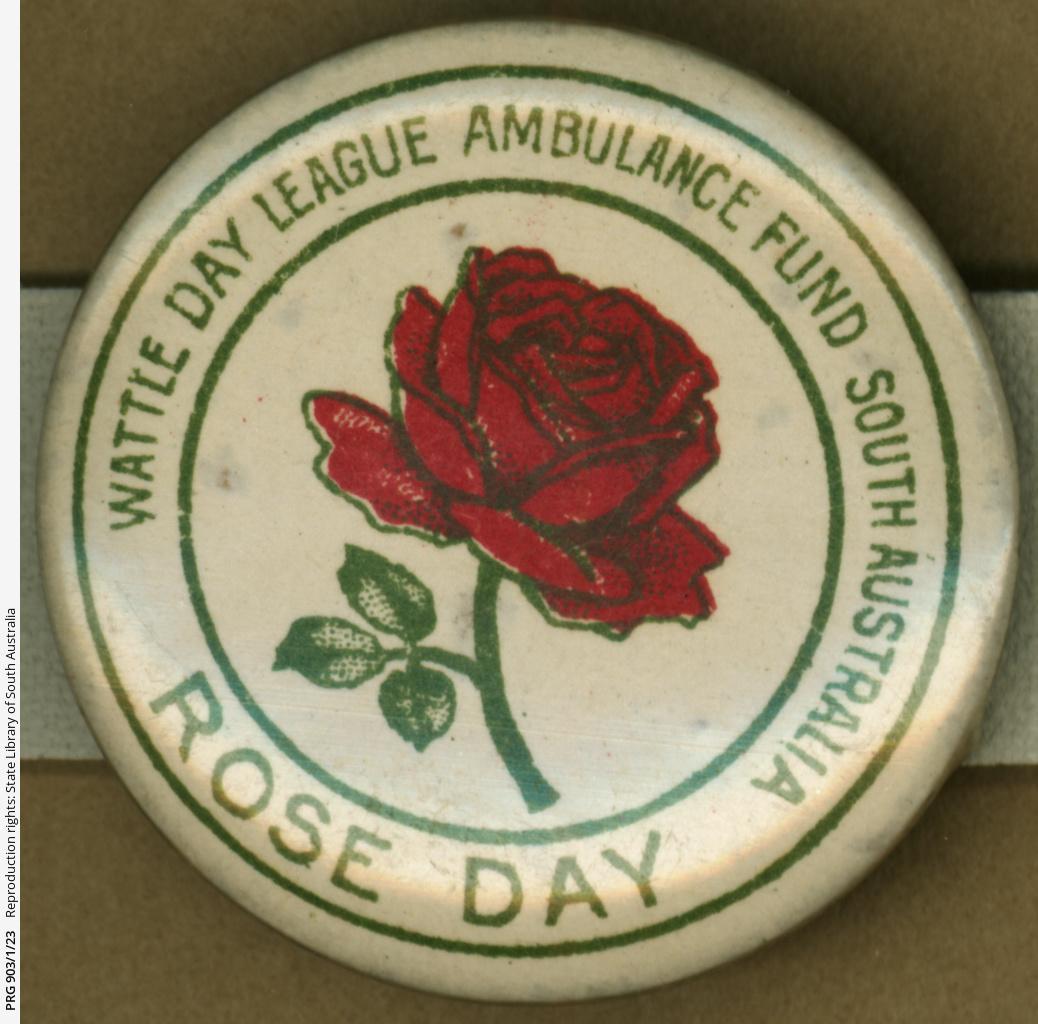

In 1909 the Wattle Day League was formed in Sydney with the intention of creating an Australian national day with a national floral emblem. Branches spread across the country. On 1 September 1910 the first National Wattle Day celebrations occurred in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. After years of debate over whether the wattle or waratah should become Australia's National emblem, the wattle joined the kangaroo and emu on the second Commonwealth Coat of Arms in 1912.

During World War One, wattle blossom became a powerful symbol of Australia, especially for military and medical personnel serving overseas. at home, sprigs of wattle and Wattle Day badges were sold to raise funds for the war effort.

The red poppy

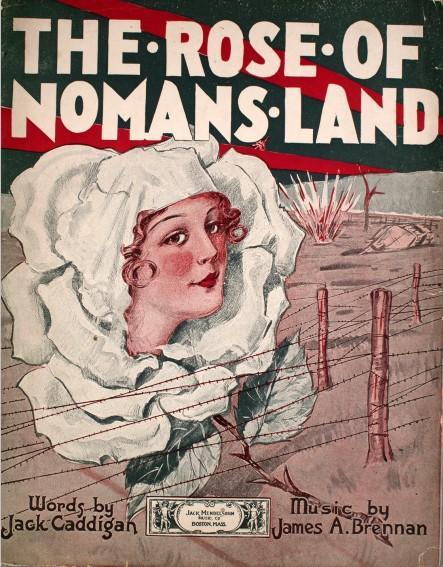

It was a poem that brought about the use of the scarlet red poppy in remembrance of World War One. 'In Flanders Field' was written in the back of an ambulance during the second battle of Ypres on the Western Front in Belgium. It was written in response to the death of a close friend who had served with Canadian doctor, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. He had noticed the profusion of red poppies around the graves of the fallen. The poem is said to have been discarded by the author but retrieved by fellow soldiers. John McRae died later in the war.

The poem was published in London's Punch magazine on 8 December 1915 and rapidly became one of the most famous poems of the era. The poppy was adopted and worn as a symbol of war and Armistice Day (now Remembrance Day) in the USA, then France, Britain and countries within the British Commonwealth, especially Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Today the poppy still commemorates the war dead.

In Flanders Field

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.~ Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae

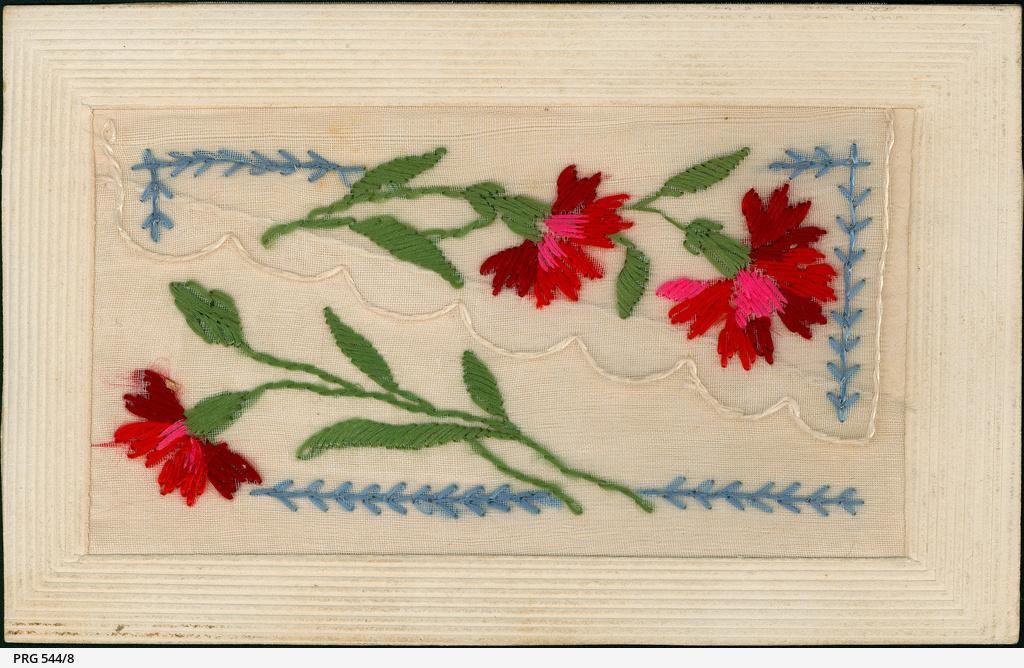

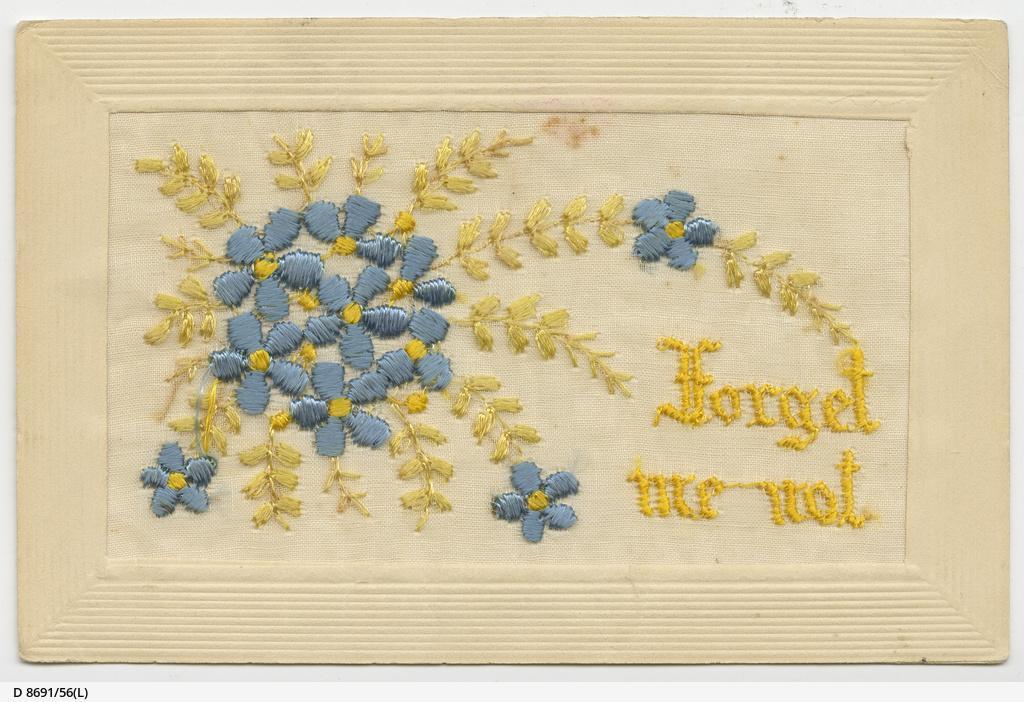

Poppies also appeared on the beautiful silk-embroidered postcards made by local women and sent back from soldiers to their mothers, sisters, sweethearts and wives. Many other flowers appeared on these cards. Forget-me-nots and pansies were especially popular. In the language of flowers, ivy signified friendship and fidelity, the wallflower stood for fidelity in adversity and zinnias messaged thoughts of absent friends. Violets stood for humility and modesty but also conveyed a secret message of faithfulness for those familiar with the messages conveyed by flowers. Pansies meant thoughts, and told the recipient that the sender was thinking of them.

The State Library holds many examples of photographs, postcards, letters and diaries of those who served in war zones, especially World War One. They tell us that for every man and woman who fell or was damaged in ways few of us can understand, there were those left behind who cared and grieved. These were also damaged, some irretrievably, by their grief and loss.

As guns and bombs and missiles once again threaten lives across the globe, it seems more important than ever, to remember the real cost of war.

Written by Isabel Story, Engagement Librarian